Image source CIO

Image source CIO

Businesses tend to think the more customers the better. And mostly that’s true. Certainly, I wouldn’t normally advocate throwing someone out of your retail business, but there are many cases where you don’t want to encourage customers to come into your store or virtual business in the first place. Thus, part of CRM (customer relationship management) involves NOT targeting customers who are too costly to serve, while focusing on developing relationships with customers who do provide profits to keep them coming back. This is the concept of CUSTOMER LIFETIME VALUE (CLV) and it sometimes involves potentially charging some customers more than others for the same service or imposing rules that reduce your cost to serve these customers you don’t want.

So, just what is CLV?

CLV is a measurement of how valuable a customer is to your company with an unlimited time span as opposed to just the first purchase. This metric helps you understand a reasonable cost per acquisition [source]

In practice, CLV involves estimating profits from customers over time based on past behaviors, including the average order value (AOV) for the customer, the average length of time customers like this continue buying products from you, and the costs incurred in servicing the customer (such as discounts necessary to drive the sale, costs of customer service, free products they receive, etc). There’s a financing component to this that represents the fact that future payments aren’t as valuable as current payments (something called net present value or NPV) due to inflation, but don’t worry too much about that as it doesn’t have a huge impact on our discussion today.

Implications of CLV calculations

Not only does CLV help determine how much you should pay to acquire customers, it determines how much you should be willing to spend on an ongoing basis to keep them.

The premise behind this concept is that all customers are not created equal. You probably already know this on a basic level, whether you put this concept into place in practice or not.

For instance, a customer might come in and buy $ 300 of merchandise while another might come in, ask lots of questions, take up enormous amounts of your time, quibble about the price, denigrate the quality, and only spend $ 8.95. The first customer is valuable, while the second customer may represent a net loss to the firm because they consumed a lot of your resources, created frustration (which might mean the customer contact person doesn’t serve the next customer as well), and then didn’t really buy anything.

This is especially true since the second customer is likely to generate negative word of mouth either by sharing their low opinions of your business or by creating negative opinions among other customers who overhear their negative interactions in your store. Or, maybe other customers had a bad experience while your staff was busy with the second customer.

Best Buy deals with this problem all the time. Customers come in to view electronics like TVs or computers, ask questions, and generally take up the sales person’s time, then buy online where they can find the product cheaper. Best Buy even uses a name for this phenomenon called showrooming.

Calculate customer value

Commonly, companies review internal sales data to divide customers into groups based on their purchase behaviors. (September 20, 2020) I posted a nice discussion of segmenting your market if you need help getting started.

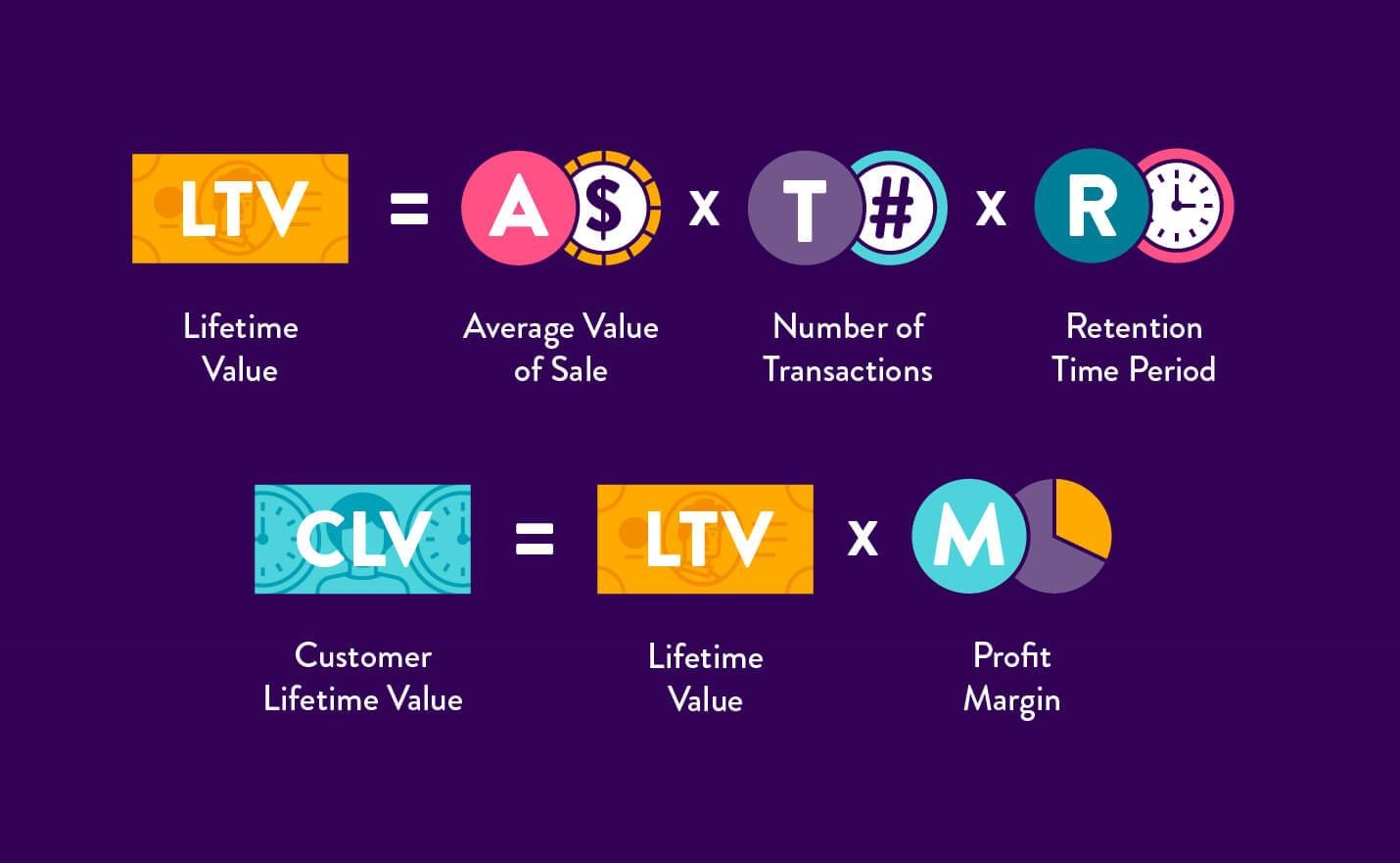

From your database, you need the average value of sales, the number of transactions, and the retention period for a given customer (see how you use this information in calculating LTV in the image below). Armed with this information, you can calculate the customer lifetime value of individual customers by using LTV and the profit margin for this type of customer, which is the difference between the profits you earn (after costs of products, discounts, etc) and your costs, such as shipping (if free), free products, customer support, marketing expenses, etc.

The next step is to divide customers into groups based on CLV. You may not see much difference, although you might see a vast difference in CLV between groups of consumers. For instance, a bank gains profits from lending out the deposits of individuals and business customers. Obviously, the higher your average deposit, the more profit the bank gains from you. Meanwhile, the bank incurs costs in terms of check handling fees, ATM fees, and the overhead needed to build and staff the physical bank.

If you analyze the bank’s customers, you likely find those high depositors product nice profits for the bank, while depositors with low balances actually cost the bank more than they earn in loan fees.

Next, what do you do with this segmentation?

Image source Clevertap

Image source Clevertap

CRM for customers you don’t want

There are 2 answers to the question of handling customers you don’t want. First, don’t advertise for this type of customer by building your messaging and strategies to limit your reach to this group of customers.

Second, use yield management (often called revenue management) to discourage them from frequenting your business.

Obviously, you never turn customers away; that’s simply bad business. Nor do you treat them shabbily, as this tends to infect other, more profitable consumer groups. You always want to create a positive experience for every customer to avoid negative word of mouth and because customer circumstances change over time. Hence the bank’s small depositor might work for a corporation someday and part of their responsibilities might include working with the bank. Don’t cut off your nose to spite your face.

Yield management optimizes profits from customers you don’t want

Let’s start with the easy one: yield management.

Yield management is a variable pricing strategy, based on understanding, anticipating, and influencing consumer behavior in order to maximize revenue or profits from a fixed, time-limited resource (such as airline seats or hotel room reservations or advertising inventory). [source]

Yield management is a means of charging customers who cost more to serve more for the service. An example is casual travelers on an airline. They demand the lowest fares, aren’t experienced so they’re slower stowing and retrieving their luggage (which causes costly delays in pushing off from the gate as these fees are a function of the time spent at the gate), unlikely to use electronic check-in (which means hiring personnel to handle their needs), and want special services that cost money, like onboard movies. Yet, airlines need these folks to fill their planes.

So the question becomes: how do we make money on these customers you don’t want?

In the airline industry, airlines respond by charging them for luggage (Spirit is now charging for carry-on luggage too), headsets, alcoholic beverages, and other amenities. One airline is even charging customers to use the lavatory. This improves the bottom line for the airline and also discourages casual travelers from using additional services that cost the firm money. Because these additional fees are less obvious at the time of booking, airlines still fill their planes, then recapture some of the cost to serve the customers via added fees.

This type of yield management is especially important for businesses like airlines, hotels, and hospitals that face very high fixed costs. In other retail firms, such as banks, fees also help discourage customers who cost the firm money without generating much profit. Hence, banks charge fees for using more than an allowed number of checks to some customers, while others get all kinds of perks. Recently, Capital One developed a campaign to encourage users of their mobile app by promoting the flexibility of the product. An obvious benefit to the firm accrues when users act as their own teller versus the costs involved in maintaining a building and paying tellers.

Your business can do the same. Charge higher fees for customers who buy in smaller quantities as is common for most e-commerce businesses that require a minimum order to qualify for free shipping. You might consider reducing costs to customers you don’t want (for instance, eliminate mailing brochures or catalogs). Other businesses limit the availability of products to customers who don’t generate sufficient revenue by, for example offering low-cost solutions with limited benefits and higher-cost solutions with more benefits. Mailchimp offers a free tier that restricts the number of subscribers and offering only basic features, while higher tiers offer an unlimited number of subscribers and more features.

Don’t attract customers you don’t want

The harder solution is to not advertise to customers you don’t want in the first place.

This is harder because most firms don’t intentionally advertise to bad customers. Despite this, your message may be something that appeals to bad customers more than good ones. Walking the thin line between attracting customers and attracting the wrong ones is a critical skill for successful businesses.

I recently worked with a services firm that sought clients from Craigslist. He was disappointed because these clients were demanding and negotiated lower fees. By using a free service, like Craigslist, to solicit business, it’s likely the customers the firm attracted didn’t understand the value of what they sought or even understand what they were asking for. Thus, it was a natural outcome of advertising where these folks were that they were bad customers.

There are a number of Chinese businesses that sell incredibly cheap products, such as Alibaba and Wish. Selling your products on these platforms makes buyers in the US think the products are cheap, so this isn’t a great way to market products if you want high lifetime value customers.

Messaging also impacts the types of customers you attract. Focusing your message on the many benefits to attract customers willing to pay higher prices is one strategy. Another in more subtle, such as using colors like gold, which implies a high cost to attract only those willing to spend more on your products. This is especially important when using PPC advertising like Google Ads, where you incur a cost for every click. Better to restrict clicks from folks who won’t find your products worth the cost than to pay for their click only to have them leave without buying anything.

Improving both messaging and the outlets carrying your message improves your ability to attract customers with a higher lifetime value. In other words, you need to fit your marketing to the type of customer you want to attract.

Know your customer

Underscoring the concept of CLV is knowledge about your customers’ buying behavior and your costs. It is critical to developing an internal marketing information system capable of providing this input into the CLV process. This takes a different kind of marketing person than in years past.

Our topic for next week will deal with what skills you should look for (or developing) in your marketing staff or consultant.

Meanwhile, please send me your questions or suggestions for future columns.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(46)