The lessons of success and failure from the world’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic should have taught every business owner how the hierarchy of decision-making should be applied if you want to make better decisions.

According to Thomas Sowell in his book “Knowledge and Decisions”, the more senior the decision-making unit, the more data they have but the less specific it is. While more data is better, specific data is required to make better decisions. Therefore, the way in which the best decisions are made is based on a hierarchy of knowledge and the allocation of ultimate decision authority to the lowest possible decision unit.

Jan Carlzon became the CEO of troubled Scandinavian Airlines and made the pivotal decision to delegate responsibility away from management and allow customer-facing staff to make decisions on the spot to resolve potential issues. Jan Carlzon’s role in turning around Scandinavian Airlines has been used as case studies by many business schools. Specifically, his choice to move decision-making down the organization’s hierarchy has been credited, with helping him turn around the fortunes of Scandinavian Airlines.

The biggest decision we have as a business owner is who should make the final decision and under what constraints.

Hierarchical Decision-Making

Think about the nation’s response to COVID-19 as an example. Superior decision-making units, such as the Federal government, are large and as such, can acquire and synthesize more data and information in their quest to create the knowledge the overall organization can use to make decisions. However, in a hierarchal organization, the higher up the decision-making unit is, the more general is their knowledge.

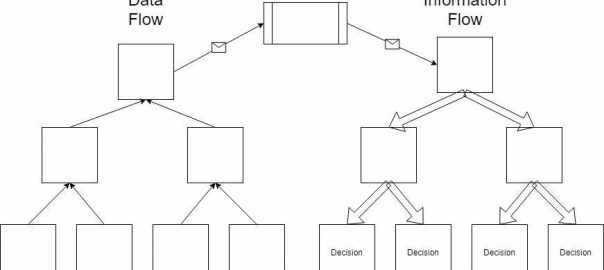

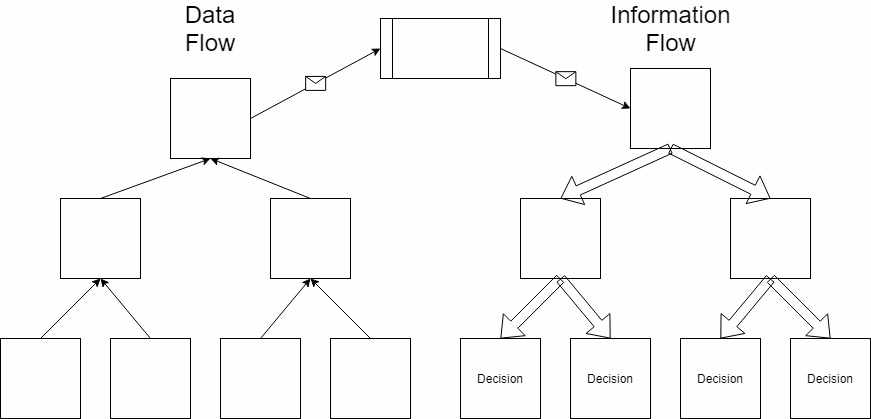

In highly functioning organizations, superior decision-making units compile information from subordinate decision-making units and codify that information to create knowledge. That knowledge is often statistical and is best used to predict larger trends. However, the collective knowledge of the superior decision-making unit is too general to be relied upon to make good decisions that will affect subordinate units.

While superior decision-making units have a broader field of view of the facts, they also have lower resolution when it comes to the details that are vital to implementing any decision. Decisions made by superior decision-making units and passed along to subordinate units for execution are frequently plagued by implementation issues.

Therefore, the role of superior decision-making units should be to take the information they have acquired from subordinate units, codify it into knowledge and then pass along that knowledge to subordinate decision-making units that have more specific information that they can apply to that more general knowledge and that will affect the implementation.

The hierarchy of knowledge decision-making process is effective because it lowers the overall cost of acquiring knowledge by eliminating the need for each subordinate unit to spend time and energy individually collecting the same data and information.

The US government has four primary decision-making units: Federal, state, county, and city. Cities are subordinate to counties; counties to the state and so on. Each senior decision-making unit takes the knowledge it has and distributes it to its subordinate units. As the more general knowledge is passed from one decision-making unit to its subordinates, each layer adds more specific information to the general knowledge received, increasing the resolution of that knowledge. The final decision-making unit, therefore, has all the general knowledge and specific information it needs to make better decisions.

This is one reason that city, county, and state governments, and not the Federal government, were tasked to define COVID-19 related restriction decisions since each subordinate decision-making unit better understood the local constraints. States, counties, and cities used general knowledge from the Federal government and applied their specific information, creating knowledge with a better resolution to facilitate the decision-making process. This knowledge was either passed along to a subordinate decision-making unit or, if they were the lowest practical decision-making unit, used to make better decisions that are far less likely to suffer from implementation issues.

Let us compare two cities in the context of COVID-19 restrictions. New York City has a high population density, lots of public transportation options including two international airports, trains, buses, and taxis, as well as a different social culture where dining out is quite the norm. New York City is a very different environment than say, the city of Seneca Falls New York that is located in the finger lakes region where I spent my vacation a few years ago. Seneca Falls is much less densely populated, has no real forms of public transportation as residents use their own vehicles to get around, and given its more rural social culture, most people eat their meals at home. The difference between these two cities is huge when it comes to the methods and probability of transmitting COVID-19 among its citizens.

Decisions regarding the imposing of restrictions to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus made at the state level decision-making unit and not at the city level would not take into consideration the specifics related to implementing statewide orders, since, at the state level, the Governor only had general knowledge. Each city or county, therefore, are better off implementing their own set of specific restrictions based on knowledge about the spread of the virus at the state level along with a set of goals and objectives from the Governor rather than a series of general restrictions mandated at the state level that cities were forced to implement.

In larger corporations, the headquarter level decision-making unit collects data and information from subordinate decision-making units, which is then processed and codified into general knowledge. This general knowledge, which includes data and information from across the organization, is then passed back down to the subordinate decision-making units with a decision-making framework, including the goals and objectives of the unit.

Therefore, Presidents pass along companywide goals and objectives as well as general knowledge to Vice-Presidents. Vice-Presidents in turn take that general information and add their more specific divisional level information to create new knowledge with a higher resolution, before passing that knowledge along to their direct reports. This process is repeated until the knowledge reaches the lowest possible practical point where the decision-making unit resides. At this point, the general knowledge has been enhanced with more specific details, allowing the final decision-making unit to make the best possible decisions.

Does your organization follow a premeditated hierarchical decision-making process?

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(16)