By Ankita Bilolikar Callahan

The term “quiet quitting” has gone viral.

What began as a TikTok trend, has worked its way into workplaces across the country. Chances are you’ve read about it, either as the idea that people are underperforming at work or that they are simply trying to maintain a work-life balance.

Whatever the case may be, it’s clear that there’s a real tension between employers and employees. A recent ResumeBuilder survey found that while the vast majority of people (74%) go above and beyond at work, 26% admit they do the bare minimum—or less. Most of those folks reported feeling burned out.

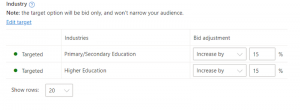

Now, companies say they are springing into action and are asking what they can do for their employees, starting with employee surveys. Many organizations are trying to solve burnout and so-called “quiet quitting” by measuring how satisfied their team members feel with their work arrangements. The problem is, employee engagement is not the same thing as employee satisfaction. And ultimately, workers need to be more than just “satisfied” to be engaged.

Here’s what organizations should consider:

Employee engagement versus employee satisfaction

Employee engagement should be a mutually beneficial exchange between the employee and the employer. Employee satisfaction, on the other hand, measures what employers should do for their employees without any expectations in return.

While both constructs are related, only employee engagement has been linked as a predictor of performance. As Lisa H. Nishii, an expert in organizational psychology at Cornell University, explains in her Diversity and Inclusion course: “You don’t want a satisfaction ring from your partner, you want an engagement ring.” The same is true for the employer-employee relationship.

What’s the difference between the two?

The academic definition of engagement refers to “an individual’s sense of purpose and focused energy, evident to others in the display of personal initiative, adaptability, effort, and persistence directed toward organizational goals.” In other words, engagement is active and when individuals are engaged, they invest their personal, cognitive, emotional, and physical energies into their work. Dr. Nishii emphasizes in her research that the investment of these active energies nets out in behaviors that are more focused and mindful.

In contrast, when employees are unengaged, they tend to withdraw and in doing so, they no longer invest those active energies. As Dr. Nishii explained in her course, they can become robotic in their work, are apathetic or detached, and become burned out. “When people disengage and become defensive, they hide their true identity, thoughts, and feelings; people go through the motions of work but do not give of themselves in their work. They are driven more by what they have to do than by what they want to do,” she says. They tend to be happy with “good enough.”

This is why employee satisfaction isn’t a holistic enough measure. While engaged individuals are curious, seeking, and passionate, satisfied individuals are content with their present state. When you conflate measuring employee satisfaction with engagement, you end up evaluating how content that individual is. This tells us nothing about their work-related energy or behaviors. It definitely doesn’t measure performance or improve business outcomes.

How to measure more than satisfaction

Next time your company decides to run an annual engagement survey, measure more than just employee satisfaction. Psychologist William Kahn’s theory of engagement establishes three dimensions that drive employee engagement:

1. Psychological meaningfulness. This dimension involves making sure jobs are structured so that they are challenging, meaningful, and provide motivating opportunities to reach potential. Dr. Nishii adds that this reinforces people’s natural tendency to respond in kind: “If you give people challenging and meaningful work and set them up for success, they will reciprocate.”

2. Psychological safety. This dimension focuses on how safe an individual feels to engage at work. Employees look for signs of whether it is safer for them to be quiet or whether they can really share their thoughts. The frequency and quality of feedback that managers seek and act upon, the transparency an individual experiences, and managers’ willingness to own up to and learn from their mistakes all play a significant role in building trust and creating psychological safety.

3. Psychological availability. This dimension centers around the bandwidth an individual has to be engaged. The Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology highlights that engagement from the previous day carries into the next and is also influenced by one’s personal life. Psychological availability centers around allowing employees to renew their energy through work-life balance. In her teachings, Dr. Nishii adds that psychological availability is about providing learning opportunities that promote confidence and a desire to improve.

Burnout and “quiet quitting” are real. Focusing efforts on employee engagement without conflating it with employee satisfaction is critical in mitigating these risks and elevating your employees’ overall experience. Engagement is a give and take, so focus on both. Measure psychological meaningfulness, safety, and availability as a starting point and commit to improving as a team.

Ankita Bilolikar Callahan is the Talent & Culture Group Director at Long Dash, a creative consultancy originally founded by The Atlantic. At Long Dash, Ankita leads recruitment, resource management, and talent management practices. She holds a Master of Science in Organizational Psychology and Business from Aston Business School and a BA in Cognitive Sciences from UC Irvine.

(17)