By Clint Rainey

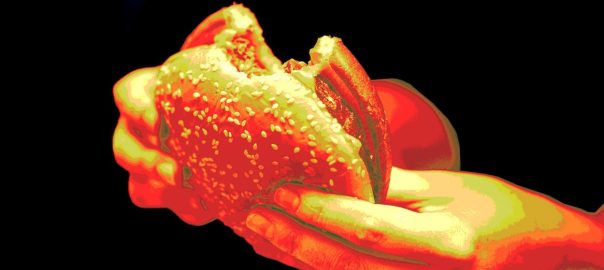

Is the beloved American fast-food-franchise model facing a reckoning?

In the past year, and more frequently in recent months, franchisees that were once big moneymakers for such brands as Burger King, McDonald’s, Popeyes, and Hardee’s have started to file for bankruptcy.

On Tuesday, a major Wendy’s franchisee—Florida-based Starboard Group—sought debt protection for 73 restaurants. In its Chapter 11 filing, Starboard wrote that both its estimated assets and liabilities were in the $1 billion-to-$10 billion range. Starboard’s CEO, Andrew Levy, faulted his Wendy’s corporate overlords for mandating that they undertake extensive remodels requiring “substantial capital expenditures” with “modest or no equivalent returns.” But he also noted what seemed to be a string of bad luck for fast-food operators collectively: a “combination of post-COVID consumer habits, ever-increasing costs to do business, and significantly higher interest rates” that have “placed many QSR [quick service restaurant] franchisees in similar situations nationwide.”

Last week, an even bigger franchise operator, Premier Kings, which has 172 Burger King outlets, and which brought in $223 million in sales last year, also declared bankruptcy, blaming “various macroeconomic factors,” including “the national impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on restaurant operations, high inflation, increased borrowing rates, and an increasingly limited qualified labor force.” (It also didn’t help that the owner, who acted as Premier Kings’ sole manager and stockholder, passed away unexpectedly months earlier.)

Both developments reinforce an increasingly worrying pattern for America’s other 100,000-plus franchise owners: A spate of sudden bankruptcies is inarguably roiling the fast-food industry.

Big corporate players like Burger King aren’t necessarily surprised. The brand, which operates 6,900 domestic locations, warned in May, at the end of its first quarter of 2023, that as many as 400 of its restaurants might have to close this year. But even before then, two large-scale, geographically diverse franchisees had already keeled over. Toms King Holdings operated 90 Burger Kings spread over four states: Virginia, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Meridian Restaurants ran 116 across an even wider territory stretching from Utah in the west, to Kansas in the east, to Canada in the north, to Mexico down south.

Elsewhere, a Hardee’s operator that once counted 145 stores in its portfolio; a franchisee at Popeyes (which has grown at a blistering pace this past year); and a longtime Pittsburgh-area McDonald’s franchisee that ran eight units have also filed for bankruptcy.

The reality is that costs have soared for restaurant operators, whose margins are notoriously thin. The pandemic left many hobbled. Inflation followed, as did the labor force’s demands for better pay; rising interest rates; and the need to update, or at minimum, digitize the customer experience. Many restaurateurs were squeezed by heavy debt levels already, and now they’re reaching the point where even the industry Goliaths with economies of scale are seeking federal aid to reorganize debts.

Just days after Burger King franchisee Premier Kings raised its white flag, Patrick Doyle, chairman of Burger King’s parent company, Restaurant Brands International, addressed this trend. He observed that the entire industry is indeed attempting to negotiate “too many risks at the same time.” Struggling franchisees were already overleveraged, and then the pandemic’s “black swan event” caused a snowball effect, and to quote Doyle’s blunt admission: “We got in trouble.”

It’s also true that the floundering franchisees that are making headlines were frequently beset by other contributing factors, making them perhaps the most vulnerable to economic headwinds. Starboard Group, for instance, had almost 100 Wendy’s restaurants in 2020, the year a lawsuit alleged that CEO Levy had used $1 million worth of Starboard’s $9 million in Paycheck Protection Program loans to finance his Montana home. And Rice Enterprises, the Pittsburgh McDonald’s operator that had been in business since 1987, filed a very “rare” bankruptcy (for the chain), after a former teenage employee sued Rice for hiring a registered sex offender as her manager, who she told the court raped her.

This is to say, perhaps the second-most-vulnerable in line should be put on notice. Because while the fast-food industry’s finances are rough and traffic has been down for the past year, franchisees’ corporate partners are finding new ways to make up for it: McDonald’s just announced that starting next year, it will hike the fees that U.S. franchisees pay by 25%—from 4% of their annual revenue to 5%. Wendy’s similarly increased its take, leading it to report in November’s earnings statement that operating profits had climbed 3.6% the previous quarter “primarily from higher franchise royalty revenue,” coupled with crafty declines in other corporate-level expenses.

As Restaurant Brands International’s Doyle laid out in his speech at the Restaurant Finance and Development Conference earlier this week: “It’s always a little dangerous to say this, but at the end of the day, our product is not Tim Hortons coffee, and great subs at Firehouse, and burgers and chicken. Our product is an economic model. As the franchisor, what we provide is a great economic opportunity for franchisees.”

(2)