By Wilfred Chan

Most of President Biden’s recent executive order on AI focused on hot-button areas like tackling safety risks and maintaining the pace of innovation. But buried in the middle of the sprawling decree was a short section on “supporting workers.” In that section, Biden directed certain federal agencies to develop new guidelines to protect workers from increasingly common AI tools in the workplace.

The guidelines that come out of the directive most likely won’t be legally enforceable. But labor advocates say the order is an important first step, demonstrating that the White House recognizes that AI isn’t merely a distant threat to workers, but a technology already being used to exploit them today.

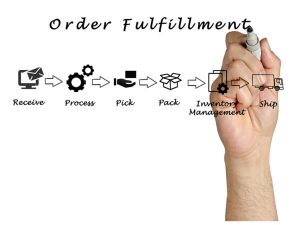

“When people think of AI and jobs, they mostly think of robots taking over our jobs, but a more insidious and pressing concern is that AI is being used to turn workers into robots,” says Nat Baldino, a policy analyst at the Center for Law and Social Policy. Biden’s executive order “allows the conversation to turn to a more systemic look at how AI is already a part of workers’ lives,” like the automated tools increasingly used to monitor and discipline low-wage workers of color in service and logistics companies, Baldino says.

Biden’s order instructs his economic advisers to “prepare and submit a report to the President on the labor-market effects of AI.” The secretary of labor, will also “develop principles and best practices to mitigate the harms and maximize the benefits of AI for workers by addressing job displacement; labor standards; workplace equity, health, and safety; and data collection,” according to the report’s executive summary.

The executive order also addressed AI used to monitor workers’ productivity. Many workers say those tools, which track physical movements or on-screen activity, add stress and fail to take into account some work activities, resulting in lower pay. Biden’s directive asks the secretary of labor to issue new guidance making sure these tools “comply with protections that ensure that workers are compensated for their hours worked.”

In a following section on civil rights, the executive order also asks the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division to hold a meeting on how to prevent discrimination by automated systems, like those increasingly used to hire and manage workers.

Baldino says steps like these “represent a paradigm shift where the federal government is saying, ‘AI isn’t actually a wild west.’ It structures job quality in a way that we already are talking about and dealing with, and we have the authority to start trying to tackle these things.”

A missed opportunity?

But some experts say the president’s order doesn’t go far enough. Veena Dubal, a University of California, Irvine law professor and expert on algorithmic management, sees the AI executive order as a missed opportunity. “It seems like the only concrete thing that will come of it is [the secretary of labor’s] report,” she says. “Workers are suffering from the harms enacted by their bosses through technology right now. How long will it take for the federal government to enforce existing laws or create new floors to address the ways in which employers use AI to pay low and erratic wages and create dangerous working conditions?”

In a research report earlier this year, Dubal found that rideshare companies like Uber use “algorithmic wage discrimination” to personalize earnings for different workers, “paying them to behave in ways that the firm desires, perhaps [paying] as little as the system determines that they may be willing to accept.” These practices could violate longstanding antitrust and civil rights laws, Dubal argued in the paper.

Uber forwarded Fast Company’s request for comment to the Flex lobbying group, which said in a statement: “App-based platforms deploy data-driven automated technologies to get people and goods where they need to go faster, safer, and more reliably while also helping maximize workers’ earning potential—and those are real wins for consumers, workers, and communities.” The White House did not respond to a request for comment.

Irene Tung, a policy researcher at the National Employment Law Project, says that the executive order seemed to be more restrained in its section on labor compared to other sections. “In the other parts of the executive order, there are calls for proposing regulations, but for the department of labor, it’s just suggesting best practices. They didn’t do anything in this particular executive order for workers other than mandate more study and reports.”

There’s also tension between the executive order’s labor section and the rest of the directive, which emphasizes maintaining the United States’ competitive edge, Baldino says.

Truly helping workers survive the age of AI would require the government to confront an uncomfortable contradiction: “The focus on competition, productivity, pace of work, speed, and innovation, often comes at the cost of job quality,” Baldino says. “There’s a huge human cost that I think has been ignored.”

Tung agrees: “Any fancy bells-and-whistles policies that only address only AI, they’re somewhat meaningless without basic labor protections.”

(3)