By Yasmin Gagne

Raad Mobrem found a mentor the old-fashioned way: A chance encounter with Kinko’s founder Paul Orfalea on the street led to a conversation about entrepreneurship and, ultimately, a long-lasting relationship that extended through Mobrem’s founding the inventory-management app, Lettuce, and eventually selling it to the financial software giant Intuit for $30 million. “We went and sat down and in, like, 15 to 30 minutes, I learned more about entrepreneurship than I had ever learned before,” Mobrem says.

But what if you’re not so lucky? With Mobrem’s latest company, Intro, he’s taking serendipity out of the equation when it comes to getting business advice from a proven success. Intro turns mentorship into a marketplace, letting users book time for video calls with a well-known businessperson for a fee. Fox example, options include $750 for a 15-minute session with Zillow cofounder Spencer Rascoff; $300 for 15 minutes with Hillary Super, former CEO of Anthropologie; and $500 to spend a little time with Joshua Viner, cofounder and former CEO of the dog-walking app, Wag. Viner surely has learned some lessons from his journey of the past several years with “the platform for busy pet parents”—what with the company’s $300 million fundraising from SoftBank before a series of misfires led the investor to pull out at a loss and then going public last year via a SPAC (which you can guess how that went).

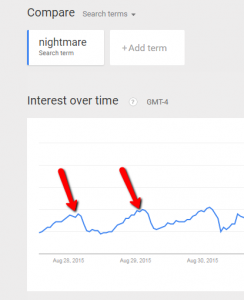

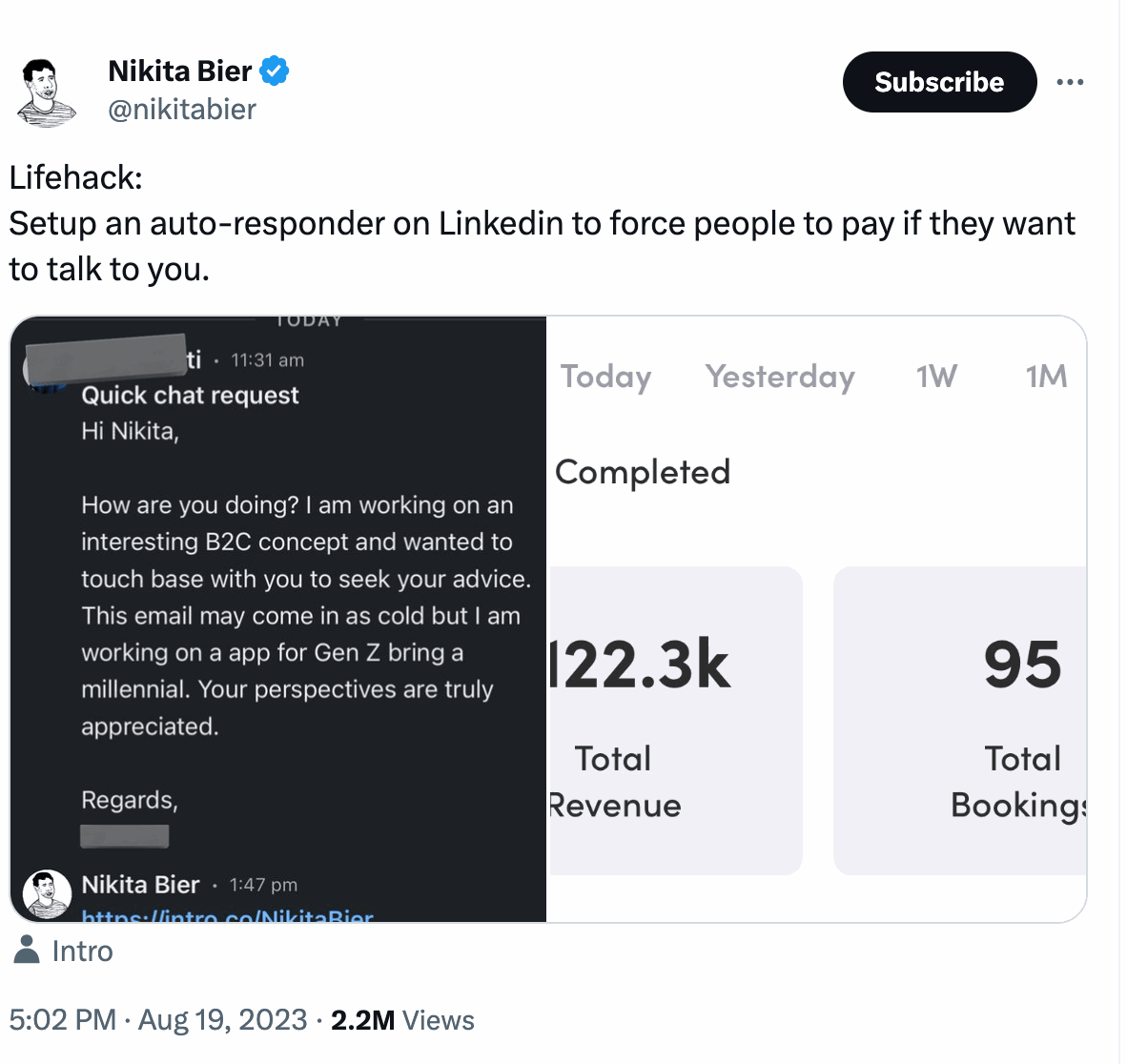

What once might have seemed like “Cameo for business” has been gathering currency among a cohort of successful founders whose digital celebrity has led them to being inundated with requests for advice via social-media direct messages. Now, when an upstart messages a would-be mentor or expert on LinkedIn or Instagram, they may well receive an auto-reply suggesting they book some time via Intro.

Perhaps it’s quaint to suggest that successful people devote whatever time they can to help others coming up after them. In fact, that’s more or less what I’m told when I ask whether there is something off-putting about their selling their time this way to those who clearly crave help.

Alex Lieberman, who cofounded media company Morning Brew and currently serves as its executive chairman, says that Intro helps him figure out who is serious about asking for help. “When people reach out to me on LinkedIn or Twitter and I respond to them and ask a follow-up question, not many get back to me. That means they didn’t actually care that much,” he says. “When someone is willing to spend money or have skin in the game to have a conversation . . . it’s just a function for showing they actually care.” That, and also that they have $400 to spend on a 15-minute session with him, or $2,100 for a monthly package that includes unlimited chat and a 90-minute video call.

While one hopes that these calls, however brief, are valuable to those paying to have them, they are undeniably remunerative for those selling their time. For example, when Nikita Bier, who started and sold two social apps to Facebook and then Discord for reportedly $100 million and a sum in the low eight figures, respectively, publicly shared his Intro dashboard last summer, it revealed he’d made $122,300 for 95 bookings.

Not everyone is quite so bold. Reddit cofounder and venture capitalist Alexis Ohanian, an investor in Intro and the rare internet-business celebrity who understands optics, charges $776 per session (his venture firm is named 776)—but he donates the money to his charitable foundation.

For many of Ohanian’s less optics-savvy (and self-aware) centimillionaire peers, one explanation for embracing Intro, and pocketing $750 for 15 minutes of basically being nice, is that they all came of age when social media was becoming such a powerful force. Hustle culture became inextricably intertwined with chasing followers, likes, and engagement, and those who were good at one often excelled at the other, too. Intro fits neatly within a mindset that values life hacks and optimizing everything. And perhaps, it’s a new way for the elite to keep score among themselves.

In a utopia, successful entrepreneurs would feel validated enough to advise or mentor others for free. But if anything, Intro reveals some of the paranoia of “people of means” (as former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz once memorably suggested the wealthiest people be called). Simply put, they don’t want to be taken advantage of. Andrew Chen, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz and an investor in Intro, charges $975 a session, but callers are not supposed to pitch their businesses to him—or any other mentor on the platform. That would be uncouth. Mobrem says that few are so gauche to do so, and the company has not had to incorporate features to deter this kind of behavior.

Intro is apparently doing well enough now that it has the classic marketplace problem of off-the-books transactions, following in the tradition of Uber, Airbnb, and countless others. (Intro’s rates vary but typically range between 10% and 30% of what experts choose to charge.) “I charge an hourly fee for my services,” says Jessica Sloane, a celebrity event planner, “so through booking 15 minutes on Intro, more people might find me, but I would encourage them to book time with me through my website—rather than through Intro—if they want more.”

Beyond people working around the system, Intro has another challenge—call it the Fight Club problem. There is a strange reticence on the part of customers to acknowledge that they’ve used the service. Even experts on the platform, like grief coach Barri Leiner Grant who says she uses Intro to book time with other experts, decline to share which ones.

But perhaps, as is suggested to me, I’m thinking about Intro all wrong. It’s not a mentoring platform, after all. One customer whom I did speak with, Howard Lerman, founder of the virtual office company Roam, says to think of Intro as a business consulting service. When he was building his startup, he booked time with Bier. “I wanted Nikita’s gut reaction to one specific feature,” Lerman says, “because he has good instincts for colors, copy, and things that you don’t really get A-B tested a ton.”

That’s the value of Intro: Being able to access experts rather than having to hire consultants. “I didn’t want connections, and I wasn’t trying to sell something,” he says. “The booking prices might seem like a big number, but don’t look at it through the lens of a consumer. You have to look at it through the lens of a business. I would pay more to hire a consultant.”

Intro, after all, calls its sellers “experts,” not mentors. Its marketing may muddle the two as does Mobrem’s founding story, but Intro gets a lot less distasteful when it’s turning the original gig work—consulting—into something even more atomized: advice by the sip. And unlike for, say, innkeepers and corporate delivery services, no one is going to feel sorry for consultants being disrupted out of work by another tech platform.

(5)