By Talib Visram

More and more companies are adding chief sustainability officers to their ranks but, despite the standardized title, the job functions can vary dramatically.

The basic function of a CSO is to help businesses achieve their social and environmental goals. But in some organizations, despite the executive-sounding titles, they’re still fringe positions; in others, they’ve become integral parts. Some CSOs may be more focused on advocacy; others on innovation. Some may report to the CEO; others may not.

Given the variabilities—and the importance—the role is at a crossroads, particularly with mandatory ESG reporting rolling out across Europe and California’s recent emissions disclosure law. As companies look to bulk up these roles to comply with the new laws, it’s also an opportunity for them to invest more in sustainability, and fuse that work into core operations.

“We increasingly see this role as fast-growing, but it is, in many ways, little understood,” says Anand Chopra-McGowan, VP and general manager at Emeritus, an ed-tech startup that partners with universities to provide accessible online educational programs. Increasingly, Emeritus’s students, many of whom are working professionals, are interested in sustainable leadership education.

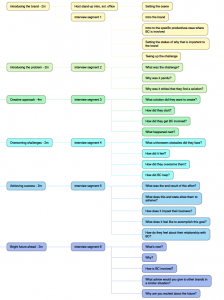

Chopra-McGowan approached London’s Imperial College to delve into the role, he says, which spurred Imperial’s Leonardo Centre, whose work focuses on sustainable transitions, to put together a new report. Over a year, the authors interviewed 37 companies, mostly multinational corporations in Europe and the U.K., including Virgin Media, Lego, Deutsche Bank, Shell, and Unilever; about half of those surveyed had appointed CSOs in the past 12 to 18 months. The researchers also used an AI-powered database to catalogue 900,000 sustainability initiatives by 9,000 companies over the past two decades.

The authors suggest what’s being done right, and recommend ways to improve the CSO role to better achieve sustainability goals—and boost financial performance.

Here are five takeaways from the report.

1. The CSO’s work should center around innovation, not advocacy

Traditionally, the CSO has been more of a communications role: to advocate for sustainable practices and to broadcast to the public that the company is engaging in such practices. “You’re trying to protect from reputational risks,” says Livio Scalvini, one of the authors, and executive director of the Leonardo Centre. “But you’re not really transforming yourself.”

While it may be a short-term branding boon, that type of work is of little use to long-term sustainability practices. Worse still, it runs the risk of greenwashing, Scalvini says, in promoting environmentally friendly practices to which a business may not be fully committed.

Instead of being an afterthought, sustainability should be at the core of what a company does. In its best form, sustainability will inform innovation, R&D, supply chain, and overall strategy. Rather than having “a sustainability strategy that’s happening in an isolated corner of the company,” Chopra-McGowan says, it’s worth developing a “more integrated business strategy that is driven by sustainability.”

Companies like Nike and Italian energy firm Enel merged innovation and sustainability long ago (the latter calling it “innovability”). Patagonia has also excelled in this area. “They’ve learned over the decades what that means in terms of embedding sustainability in the way that they run the business,” says Maurizio Zollo, another coauthor, and the Leonardo Centre’s scientific director.

2. Integrating sustainability achieves better financial performance

Putting sustainability at the core is easier said than done, particularly when shareholders are focused on profits. “[Companies] have to show a narrative that is powerful for investors,” Scalvini says.

But the authors found a strong correlation between centering sustainability and financial performance. Companies where sustainability was linked to overall business strategy and innovation outperformed the S&P 500 index over the last 10 years by 92%. Those that chiefly focused on advocacy underperformed the index by 70%. That’s a 162% gap between the best and worst companies with respect to sustainability.

“Greenwashing is clearly damaging reputations,” Scalvini says. But it’s also hurting profits. “If you are just talking and not walking, you underperform.”

3. Where the CSO is positioned within the organization is critical

Titles can be deceiving. “They call themselves chief sustainabilityoOfficers, but they do not necessarily sit in the C-suite,” Zollo says. Because the role has traditionally been one of advocacy, Zollo says the “historical positioning” has been to report to the communications or PR department. But that will naturally bring different results.

More recently, companies have the CSO reporting to an executive in the C-Suite—over half of the companies surveyed have this setup—or as a C-Suite position itself. “It’s a lot more powerful internally because they have the ear of the CEO,” Zollo says. In other words, they can have a larger influence in ideating innovation and strategy.

The authors also say a CSO’s collaboration can stretch beyond the borders of the company. Though it’s a novel and controversial concept, CSOs can and should work with competitors to align on sustainability goals, in order to improve the entire industry. Zollo says Patagonia has spearheaded that, working with competitors to agree on more sustainable materials. That means “everyone raises the bar and is able to achieve a lower environmental impact,” he says. They can then compete with rivals in more creative ways.

4. Sustainability reporting is crucial to measuring your own progress

In Europe and the U.K., businesses are required by law to submit disclosures that report their ESG goals and their progress toward them, including details like direct and indirect carbon emissions. California also recently passed laws requiring reporting (it may also be required nationally, pending the approval of SEC proposals).

This is the biggest source of annoyance for CSOs, as it’s a massive, cumbersome undertaking especially for smaller teams. “They responded very clearly that it’s a huge pain,” Zollo says.

Chopra-McGowan hosted a dinner with a dozen CSOs after the report’s release, and he says the disclosure burden was a common theme. Many of them want to be doing the more innovative work, but the overload of reporting has become a barrier to achieving more ambitious targets—say, from net-zero to net-positive goals.

But reporting can be an aid to long-term goals, Scalvini says, because it helps a company understand where they are now. “Reporting is the baseline,” he says. “It’s like saying, ‘I’ve got this pain that I have to produce financial reports. And I prefer to go to a board or to an investor without any reporting.’”

Companies should guard against disclosures being the sole purpose of a CSO’s team, because it robs them of any competitive edge. “Compliance, by definition, means that everyone has to do the same thing,” Zollo says. “A company that is focusing its sustainability efforts on just compliance basically means it is giving up.”

5. Educating the workforce is key—but that’s not the CSO’s job

This mammoth list of tasks on CSO agendas likely feels daunting. “We are asking the CSOs to be heroes,” Scalvini says. Unlike typical jobs, which are set up to appease one set of stakeholders—whether customers or employees or shareholders—CSOs “have to engage all the factions, and bring these people around the table to design a shared mission.”

In order for the company to be successful in reach its sustainability goals, the entire workforce needs to have a certain knowledge of sustainability. Yet, this education is often the responsibility of the CSO—a huge undertaking given an overall lack of awareness, and the already-full plates of CSOs.

To relieve that pressure, businesses need to invest in sustainability education, of which there are various courses available. “If we do a better job of training our workforce and our leaders as to why this stuff is so important,” Chopra-McGowan says, “then it becomes much easier to actually do some of these compliance things.”

(4)