At my previous job, I was always some combination of tired and bored when it was time to work. If I wasn’t sleeping, I was scrolling through the internet like a thirsty zombie looking for my next dopamine hit. Did I get any work done? Yes, but only with deadlines breathing down my neck.

I knew I had to make a change, so I frantically searched for productivity videos and came across Brendon Burchard, bestselling author and high-performance coach. There was one particular video in which he talked about how high performers generate energy on command instead of waiting for energy.

He used this analogy: A power plant doesn’t have or store energy; it generates energy. So, every 50 minutes, Brendon generates energy by taking deep breaths, cupping his hands, and tapping his body inch by inch. First his hands (fingertips to shoulders), then his legs (ankle to butt), then his back.

I tried his method, but it didn’t work for me—at least not immediately.

So, I decided to create my own experiment to generate energy using the skeleton of his framework: doing something after a given period of time. Instead of tapping my body every 50 minutes, I’d do a new activity every hour.

Experiment setup

The reason body tapping and walks failed me was because the inertia was too great to overcome, and energy took time to kick in. If you’ve tried walking when sleepy, you’ll notice the grogginess doesn’t go away immediately. You have to walk for a while before it wears off. I knew I needed activities that had low barrier-to-entry and immediate reward.

This boiled down to two types of activities:

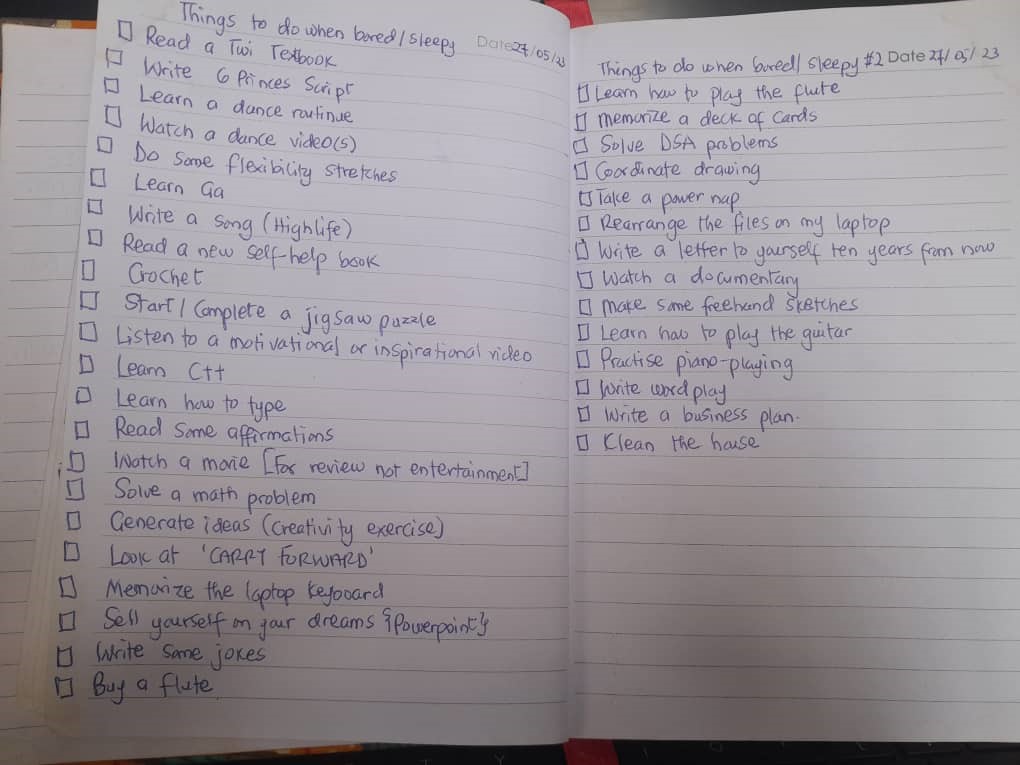

- Things I’ve always wanted to try or had to do but never really had a chance to do (my bucket list)

- Things I naturally enjoy doing

Think to yourself: What activities do I currently like doing? What do I do in my free time? What activities have I always fantasized about doing? What’s on my bucket list? Write it all down in your favorite note-taking app (or by hand, like I did.)

Rules of the experiment

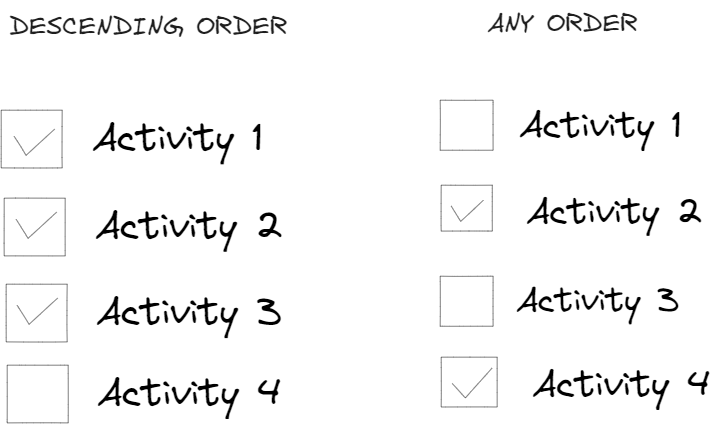

Even though I wrote the list in no particular order, I made myself go through it in descending order. The rule was never to skip a previous activity unless it was unavailable or couldn’t be performed because of time and location. I wanted to give myself the opportunity to try everything on my list. Here are the other rules I made for myself.

- Each activity is to be performed once at each point in time

- Each activity shouldn’t exceed the allocated time

- If you get new ideas, insert them at the bottom regardless of how enticing they are.

Time for each activity

Each activity lasted 10-15 minutes. So after an hour, I’d give myself a 10-15 minute break. If I couldn’t go the full hour, I’d use a variation of the Pomodoro Technique.

| Work for | Break for | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | 20 mins | 5 mins |

| Round 2 | 20 mins | 5 mins |

| Round 3 | 20 mins | 10-15 mins |

If I felt sleepy before the 20 minutes hit, I’d reduce the time further, until I found a time that I could go for without zoning out, even if it was two minutes.

Metrics

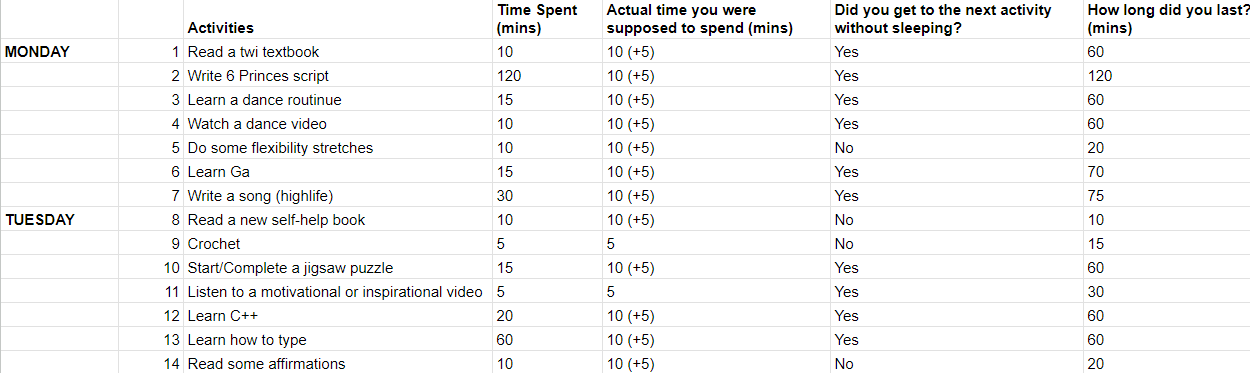

I tracked the following metrics during the experiment, sometimes on sticky notes and sometimes in Excel.

- Activities performed

- Time spent performing them

- Actual time I was supposed to spend on them

- Whether or not I slept before the next activity

- How long I lasted

I used Toggl to track the time I spent actively working—that’s what informed the How long did you last? column. Toggl generates reports you can mine for insights, which is a nice perk.

The results

Initially, I was skeptical about this experiment actually curing my sleepiness/boredom, but I was shocked by the drastic increase in energy after giving it a try. Throughout the weeks, I tweaked the experiment and tested it against the control.

Iteration

Result

Problem encountered

Solution

First (rigid list)

Increased energy

Boredom and reluctance

Choose any activity from the list

Second (flexible list)

Increased energy

Wasted time and analysis paralysis

Reduce the list to activities that wake me up longer

Third (one activity)

Increased energy

Context switching

Do the thing(s) I gravitate towards

First iteration (rigid list)

I realized I had increased energy. I was napping less and less during the day. But I encountered a new set of problems: boredom and reluctance. I was dreading some of the activities I had to do. Certain moods and environments weren’t meant for some activities.

- I would go into some activities unsure I would like them and end up liking them and even exceeding time.

- I would go into some activities unsure I would like them and end up not liking them and waiting impatiently for the timer to go off.

- Some activities were unfavorable for the environment I was in. For example, I couldn’t do flexibility stretches at work. I had to find possible alternatives, which ended up taking all the time and then some.

So, I tweaked the experiment. I changed the “descending order rule” to an “any order rule.” Now, the list was under my control. After an hour of working, I picked any activity based on interest and environment.

Second iteration (flexible list)

Throwing spontaneity into the mix made me less bored and reluctant. But— surprise!—another problem sprung up: wasted time caused by analysis paralysis. Because I had too many choices, I spent time deciding which activity to do instead of actually doing the activity.

This time, I reduced the list of activities and only kept the ones that woke me up for longer or that I knew I liked doing.

Third iteration (one activity)

After narrowing the list down, I realized I was getting tired of context switching. I was performing some activities more than others because I liked them so much I didn’t want to do anything else.

Sometimes it was typing, sometimes it was scriptwriting. Because I was getting better at typing, I would type for ages. When it got boring (it rarely did), I would switch to another task.

Should you try this experiment?

If you want to try this experiment, here’s what you should know.

Pros

- Increased energy: When you give yourself a fun reward after an intense period of focus, you create consistency and generate energy. Extra points if the activity has been on your bucket list for so long because you keep telling yourself you’ll sorta, one day, maybe do it in the future. There are times when I’ve gone 3+ hours without needing the 15-minute break. It’s exciting.

- New skills: It’s easy to build a skill in something you like doing. I learned touch typing, and my words-per-minute and accuracy have increased.

- Exercise focus muscles/get things done: Turns out you can get a lot done in 30 minutes. With attention stealers breathing down our necks, training yourself to focus is a valuable skill. I started a script I’d been procrastinating on for ages. I didn’t complete it, but I got further along than I would have if I hadn’t done the experiment.

Cons

- Going overboard: You might get carried away by some activities. This happened more times than I can count. I couldn’t stick to 10 minutes for some activities. When I added the five minutes of extra time, it still wasn’t enough. I snoozed the alarm several times until I had finished indulging myself. Not great for work productivity.

How to make the most of the experiment

After doing some version of this experiment several times, here’s what I’d recommend you do to optimize your experience.

- Don’t go beyond the scheduled time: Of all the rules I set for myself, this was the only one I didn’t follow completely. If you’re concerned about productivity, your word should be your bond. Break is over means break is over.

- Measure religiously: If you’re concerned about increasing your energy, you need to be observant about which activities light you up or keep you awake for when you have to remove some activities from your list. Before you start the experiment, take a week to track your peak hours and hours you feel a dip in energy. While performing the experiment, observe the times you feel sleepy or bored, if there are any, and see if there are any improvements.

- Set up the activities for the day ahead of time: Another way to combat wasted time and analysis paralysis is to pick activities you want to perform the day before or early that morning. But if you’re the go-with-the-flow kind of person, ignore this.

- Clean your list before starting: After the brain dump, I just went ahead with the experiment. You can make things easier by arranging the items on your list based on interest (the experiment will reveal whether or not you were right). Also, if you know you’re going to be in the office while doing this, write an alternative or remove any at-home-only items altogether.

Energy can be generated

Our biggest asset when it comes to managing our time is our energy. Lots of time with no energy to perform a task is a waste of time. While we have our natural peak hours, we can also generate energy during those hours when we’re lacking energy or motivation and still need to get things done.

Try this experiment, and let me know how it goes.

—Esther Kumi for Zapier

This article orginally appeared on Zapier’s blog and is reprinted with permission.

(8)