As the price of eggs, dairy, and gas shot up in 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022. With the backdrop of the highest inflation levels in four decades, the bill’s name appeared to describe pretty succinctly what it set out to do.

But it’s widely accepted that the IRA was first and foremost a climate resiliency package, comprising initiatives for clean energy, clean transport, and tax credits for consumers and businesses to invest in items like EVs, energy-efficient stoves, and sustainable aviation fuel.

Still, a year after its passage, inflation has dropped considerably—from its peak of 9.1% in June 2022, to 3.2% in July 2023. Some economists believe that while the IRA may have long-term deflationary results, the current decline is rooted in other causes. But others say the bill has already impacted the decline, illustrating a new model to tackle inflation that’s contrary to the conventional wisdom.

The government was upfront about the bill’s goals; the White House’s IRA guidebook touted it as “the most significant action Congress has taken on clean energy and climate change in the nation’s history,” only later noting it would “help . . . tackle inflation by reducing the deficit.” No Republicans voted for it, lamenting that it focused on the wrong issue. “Rather than listening to the American people who are suffering from inflation, Democrats have voted for a liberal wish list,” Senator Mitt Romney said.

“A climate change bill, paired with a bunch of deficit reduction” is how Nirupama Rao, assistant professor of business economics and public policy at the University of Michigan, characterizes the IRA. “This was a bit of well-placed marketing to call it the Inflation Reduction Act,” she says.

She’s not alone in that thinking. “Notwithstanding the name, I don’t think anyone believes that its main purpose was to reduce inflation,” says Shai Akabas, executive director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “Although it was certainly a relevant economic event occurring at the time to latch it onto.”

“A very weird time”

Inflation levels in 2022 were the highest they’d been since 1981. Prices surged between December 2021 and December 2022, driving up the cost of eggs by 55%, gas by 32%, and airfares by 29%.

The causes seemed to fit the classic definition of inflation: surplus demand for goods relative to the available supply. Inflation is more likely when the economy is strong and employment is high, and there’s money flowing around that lets people spend more, overwhelming the rate at which goods can be produced.

All of those circumstances were present in recent years. “It [was] a very weird time,” Rao says. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a strange shift in consumer behaviors, when “people weren’t getting haircuts,” she says, “they were instead buying fridges.” Meanwhile, the government poured money into the economy to buoy it, via stimulus packages like the American Rescue Plan. On the supply side, the pandemic disrupted supply chains, and the Ukraine war reduced energy stocks. The inflationary results were clear. The rate started shooting up in February 2021, reaching 5% by the summer, and the peak of 9.1% in June 2022.

“Most economists, myself included, did not adequately appreciate how large these disruptions would be, and how they would push supply chains so far beyond the normal range of fluctuations,” says Steven Fazzari, distinguished professor of economics at Washington University in St. Louis.

A climate package was unlikely to immediately drive down this inflation. But that’s not to say it didn’t have the potential to help over time. Boosting energy supplies with investments in renewables should create resiliency and ultimately drive down prices in the long term. And that appeared to be the intention: The $369 billion for climate incentives was earmarked over a stretch of 10 years, and the government forecasted it would reduce the federal deficit by $237 billion over that time. (The theory is that bringing down the deficit reduces the amount of money in circulation, and so cools demand.)

But the short term is another story. “I’m not sure any of those things could conceivably reduce inflation in the first two or three years after passage,” Rao says. In its forecast, the Congressional Budget Office predicted a relatively low deficit reduction of $21 billion, which Penn’s Wharton School of Business noted would have an impact on inflation “statistically indistinct from zero.”

There were other aspects of the IRA intended to raise money to pay for the climate investments: a $64 billion Obamacare extension and direct caps on drug prices, a minimum corporate tax of 15%, and more IRS enforcement. But those haven’t yet had their full impact. The drug component has been tied up in courts, and the tax rate hasn’t affected as many businesses as hoped. “It was really the pay-fors that were going to help reduce inflation in the near term,” Rao says, “and those have not been realized.”

“Team Transitory”

Still, at a current rate of 3.2%, there’s no doubt inflation has dropped significantly. “There are a lot of factors playing into what’s going on with inflation right now,” Akabas says. “And I don’t think the IRA is foremost among them.”

He says much of it is simply due to time. The economy had to wait for issues with the supply chain and oil and gas to work their kinks out, and for public spending like the American Rescue Plan to “[flush] its way through the system,” he says, thus leaving less money in consumers’ hands and stabilizing demand.

Economists have been fighting since the pandemic about whether the inflation was “transitory”—that it would dissipate on its own—or that it was a permanent new normal driven by changes to the economy that required more aggressive measures to mitigate. “I suppose I would say ‘team transitory’ was right all along,” Fazzari says. “It’s just that the time definition of ‘transitory’ was several years rather than several months.”

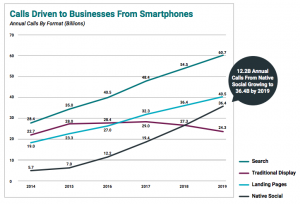

Additionally, the Fed raised interest rates 11 times between March 2022 and July 2023, a longtime solution for reducing inflation. The idea is that increasing rates discourages loans, which cuts back on consumer spending and evens out demand with supply.

But doing so intentionally aims to tip unemployment slightly higher. With fewer workers employed, there is less push for higher wages, which helps to decrease prices of goods.

“A false trade-off”

But this time, just as inflation has declined, unemployment has also remained low, which is surprising. That’s proof that the IRA has been effective in lowering inflation, even in the short term, according to Rakeen Mabud, chief economist and managing director of policy and research at Groundwork Collaborative, a left-leaning economic activist group.

“The Biden administration and Congress really appreciate that there is a false trade-off between lower unemployment and lower inflation,” she says. “Any of the good that we’re seeing in the economy is in spite of the Fed’s actions, rather than because of it.” For Mabud, the IRA has demonstrated a way to use fiscal policy to solve inflation, injecting money into energy and healthcare to bring down some of the highest drivers of inflation and cost of living.

She says there’s more to do. Just as the government targeted drug and fossil fuel companies by capping drug prices and boosting renewable alternatives, it could do the same with other huge drivers of inflation, like housing. In Minneapolis, for example, inflation has dropped to the lowest for any metro region in the country, at least partly because the government invested millions in rental assistance and subsidies for development. Residents now pay the lowest share of their income on housing relative to all other similar cities.

Still, it’s hard to quantify how much of inflation’s drop was due to the IRA, given that many of the healthcare and climate subsidies haven’t even kicked in yet, some not due to roll out until 2025. But Mabud says the big takeaway is that it’s possible to use a different government-forward approach to inflation management. “It really marks a turning point in the way that people are thinking about inflation,” she says.

Such fiscal policies may be key to driving down the more persistent elements of inflation that are still present, including housing, education, and transport. Core inflation, which removes some of the more volatile prices like food and energy, remains elevated at 4.7%. It’s also known as “sticky” inflation because it’s harder to budge; it never went up as much, and hasn’t come down as much either.

“The hardest part of the battle may be yet to come,” Akabas says. “We’ll see what that looks like over the rest of this year and into next.” Forecasts predict it will likely be 2025 by the time core inflation reaches 2%.

If measured by inflation, the IRA has been a success. But that’s not the best way to look at it. “I’m not sure that’s the right scoreboard for this piece of legislation,” Rao says. If judged by climate investment, it’s been “wildly successful.” It has had a huge uptake—more than expected—from businesses and consumers. That could ultimately make it more expensive to pay for, taking longer to reduce the deficit. But that may be a necessary evil. “Is more always better?” she asks. “That might be true when it comes to climate change.”

(4)