I read a great post from BCG about the evolution of organizations equating adaptation in the biology of “survival of the fittest“. Like the stunning lioness above, survival depends on both adaption and community (a point missed in the BCG evaluation). Today, I’ll discuss how biology provides insights into how organizations work.

Survival of the fittest

Organizations face change, uncertainty, and complexity in their environments just as animals are challenged by changes to the natural environment. New competitors emerge, resources change, sources of revenue (food) appear or disappear or change their tastes …

Organizations face a survival of the fittest situation that favors those who adapt to the changing environment.

Don’t believe me?

Check out this quote from the study by BCG:

To answer that question [how are organizations faring in facing challenges presented by a changing environment], we investigated the longevity of more than 30,000 public firms in the United States over a 50-year span. The results are stark: Businesses are disappearing faster than ever before. Public companies have a one in three chance of being delisted in the next five years, whether because of bankruptcy, liquidation, M&A, or other causes. That’s six times the delisting rate of companies 40 years ago. Although we may perceive corporations as enduring institutions, they now die, on average, at a younger age than their employees. And the rise in mortality applies regardless of size, age, or sector. Neither scale nor experience guards against an early demise.

Applying biology to enhance our understanding of these complex biological systems provides enhanced understanding that might improve survival rates of these organizations.

Chaos theory comes from complex adaptive systems. The “butterfly effect” is probably the best known example of the butterfly effect as it appears prominently in Jurassic Park. In simple terms, the butterfly effect proposes that small changes in the environment — like a butterfly’s wings distorting the air around it — can produce large, difficult to predict changes — such as a hurricane thousands of miles away.

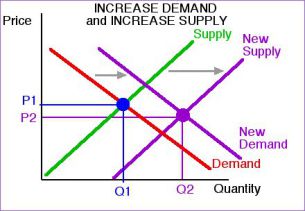

Chaos theory also proposes a non-linear interaction between causes and effects, negating much in the way we view information in organizations. Think of the familiar supply-demand curves that are totally linear — even though there’s sometimes a little curve in the relationship between supply and demand.

Image courtesy of Clubraf

Compare that with the non-linear relationships envisioned by chaos theory, which are 3 dimensional relationships across a broad number of factors containing both direct and mediated relationships suggesting a wide variety of factors impact survival of an organization.

A real world example of chaos theory is the impact the home mortgage crisis in the US had on the global economies of most developed countries. Because of derivatives and other fancy financial instruments, mortgage defaults quickly spread through the stock market, dampened consumer demand, destroyed consumer confidence, reached every industry causing cutbacks and layoffs, and spread to England, France, Germany …

BCG’s recommendations for handling change in complex environments are all variants of diversification — by diversifying into ancillary products, modularizing your business operations, creating redundancy within your operations, reducing uncertainty, and using feedback loops to increase adaptability, BCG believes organizations maximize survival.

Here, I strongly differ with the interpretation of survival of the fittest in organizations underpinned by notions of sensing, adapting, collaborating, and surviving.

Sensing, adapting, collaborating, and survival of the fittest

Sensing

I’ve worked with a large number of organizations across a wide swath of industries and none of them do enough to sense what’s going on in the environment around them. Too much of their analytics budget is spend on mapping performance and too little on what’s going on outside the firm — with customers and prospects, with competitors, with technology, and economics.

A great example of where sensing broke down is the oil shortages of the mid ’70s. Major players in oil exploration and refining like BP and Exxon and car manufacturers failed to anticipate the impact of political changes in the Middle East on oil production in time to adjust their long-term planning. Only Shell saw the potential for OPEC to curtail production to the point where world prices skyrocketed as supply shrank.

Both industries, as well as heavy consumers like manufacturers, suffered devastating losses that rippled through the world economy. Faced with competitors like Toyota and Datsun (now Nissan) who produced smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, the US auto industry never recovered from its failure to sense changes in the environment.

Adapting

Adapting has always been the dominant strategy in the survival of the fittest.

Instead of focusing on disruptive innovation, too many organizations seek much safer improvements in existing products. Yet, disruptive innovations and a willingness to engage in cannibalization of existing markets, produces returns that pale those possible through improvements.

But, innovation for innovation’s sake doesn’t ensure survival of the fittest. When combined with sensing, adaptation and innovation create opportunities for serious growth just as sensing and adapting to a new predator ensure growth and survival of an animal population.

While animals don’t control adaptation, businesses certainly do. And, whether those adaptations are new products, new processes, new cultures, or new alliances, adaptation ensures survival — at a cost.

The costs of adaptation are high and many adaptations don’t work just as genetic changes don’t always prepare a species to succeed.

Thus, adaptations not only cost time and money, they’re risky. Risk is anathema in many organizations where a short-run mentality determines decisions because innovations take time to improve the health of the organization or might fail completely. What these organizations fail to understand is that it’s their fear of failure that determines they won’t survive in the long-run.

Think of the story of the MAC. A totally disruptive product that cost Apple lots of time and money that might have been used to improve the LISA. But all Apple did by improving the LISA was make incremental changes to be a little better than their competition. There wasn’t a clear, sustainable superiority that provided for the long-run survival of Apple in such incremental changes. A major improvement at HP or entrance of a new competitor could have wiped Apple off the face of the planet.

By disrupting the market with the MAC (and it’s phenomenally effective advertising campaign), Apple gave consumers a value-proposition that resonated and through down the gauntlet to competitors challenging them to respond — something they failed to do effectively. So, Apple survived to bring us the tablet, iPod, smartphone, and other disruptive innovations.

Adapt to survive and survive through adaptability!

Collaborate

In the natural world, species live in complex ecosystems characterized by interrelationships between species and within groups. Lionesses feed on antelopes; bringing their prey back for cubs so they can grow into adults.

Why would we think the business world would be any different?

Businesses live in an ecosystem composed of suppliers, competitors, channel partners, customers, government, and society at large. Rather than competing, businesses must develop relationships that aid their long-term survival. Cooptition rather than competition. Such collaborations bring value to everyone in the value chain from vendors to customers.

Working with a client, I discovered a great example of collaboration in survival of the fittest.

A supplier anticipated an employee strike that would leave his customers without product and their customers dissatisfied. In advance, the supplier arranged for a competitor to supply his customers so their operations were unaffected by the strike. Rather than costing him business, concern for his customers cemented the relationship between the supplier and his customers. When the strike was settled, his customers came back with stronger commitments to their ongoing relationship.

Similarly, companies cooperate with competitors to expand the market for their products. An example is the electric car industry where competitors agreed on a single charging port making it more cost effective to provide recharging stations and encouraging more stations. Even Tesla, with their rapid recharging unit, create their cars to use the standard charging station. Ubiquitous charging = more aggregate demand = more stations = more electric cars sold.

I wish more companies would recognize the inherent value in collaborating for customer benefits.

Survival of the fittest

While animals have little ability to control survival of the species, business do. They must determine what factors they control (and optimize them) and which they don’t (and adapt to them).

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community(34)