Even though everyone’s trying to do their best right now, it’s tough — for both leaders and team members. Just making the right decisions every day is confusing because so many things are up in the air, either moving too quickly or not moving at all.

Conscientious people are willing to work very hard and strive to get everything right, even under adverse conditions. They tend not to complain or ask for help. But it’s important for leaders to be aware that even if team members aren’t complaining, asking for resources or support, or visibly dropping the ball, it doesn’t mean they’re okay.

How Do Conscientious People Think?

Most people don’t like to say that they’re having a problem. They may not want to disappoint anyone. Maybe they think they should know the answer, or they assume it’s their job to figure things out. Perhaps they believe it shows weakness to admit they don’t know what to do. Or, as is increasingly common these days, team members know their leaders are already stressed and have more important things to worry about, so they tend to hunker down and just try harder rather than disturbing their managers.

Sometimes those approaches work. It’s good to figure things out, to be curious, resourceful, and self-managing. But if you’re a leader, you probably experience situations when it would be much better if employees would just come check with you. Then you’d have the chance to review the situation and give a quick answer or make a rapid decision, avoiding back-and-forth and wasted time. Given your broader organizational perspective, you might recognize that other resources are needed or realize that someone else should be picking up some of the slack.

But if team members are being conscientious, they’re probably trying not to add to your load with their problems. So even though you don’t want to be a micromanager or for them to feel as if you’re checking up on them, especially during this disrupted time, it’s incumbent on you to check in with greater frequency than usual.

Ask for the Score

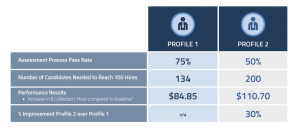

One relatively non-threatening way to do this, rather than intervening immediately, is to show curiosity and interest in how things are going. Try asking team members to grade the situation as if it were a school test, up to 100 percent. You’ll find that people often pick what sounds like a reasonable number — say, between 75 and 90 — to show that things are going reasonably well, from fair to good; and, since you know your people, you’ll know who’s inclined toward grade inflation.

Unless team members say they’re scoring 100, you can ask them what it would take to move their grade up a few points — maybe two or three if they’re in the 90+ range, or even as much as 10 points if their overall score is hovering in the 70s. They may describe something that’s worrying them or in their way. Once they start talking about their improvement differential, you can provide useful suggestions or offer to intervene as necessary. Even if they believe they’re operating at an A++ level, you may be able to ask about what would work even better or at less cost to themselves or the business if they face the same situation again.

As a conscientious manager yourself, you may want your team members to come to you with questions and be willing to draw out their concerns. But it’s also extremely common for good managers to be unwilling to expose their own weaknesses or concerns by asking for help from their own leaders.

Avoid the “Doom Loop”

When responsible, conscientious people believe they should know all the answers, and that every problem is theirs to solve, they naturally feel that they shouldn’t seek help, that all they need to do is dig deeper and push a little harder. But if you’re the one digging and pushing, how can you tell when you should be asking for help? Consider how you’d see things if your good colleague was in your situation instead of you. If your good colleague were having your problem, would you encourage them to get help or go involve the boss?

I often suggest to clients that if they’ve gone round and round in the same spot for more than 20 minutes, they’re officially wasting their own time and resources, and they should get in touch with me, their boss, or a good colleague and talk it out. A few minutes of thoughtful discussion can often get you out of the doom loop or make it clear that an issue needs more senior attention. Then it’s no longer just your problem or about your weakness — it’s a business problem.

Conscientious people have the right idea: They should challenge themselves first, do the necessary research and cudgel their brains. But they need to know when to take action and share the problem with others. If they don’t, they’re unknowingly opening the organization to potential risk by denying their leadership the option of weighing in when doing so would be valuable. Sometimes the most conscientious, responsible thing to do is to ask for help.

Business & Finance Articles on Business 2 Community

(39)