After only a year and a half, Tremaine Emory is leaving his position as creative director at the streetwear giant, Supreme. In his resignation letter, he said he believed that “systemic racism was at play within the structure of Supreme.”

Supreme was founded by James Jebbia 29 years ago. In 2020, VF Corp—which owns North Face-—acquired Supreme in a deal that valued the brand at $2.1 billion. Jebbia stayed on as CEO, but appointed Emory as creative director. Today, Supreme issued a statement acknowledging Emory’s departure. “This was the first time in 30 years where the company brought in a creative director,” it reads. “We are disappointed it did not work out with Tremaine and wish him the best of luck going forward.”

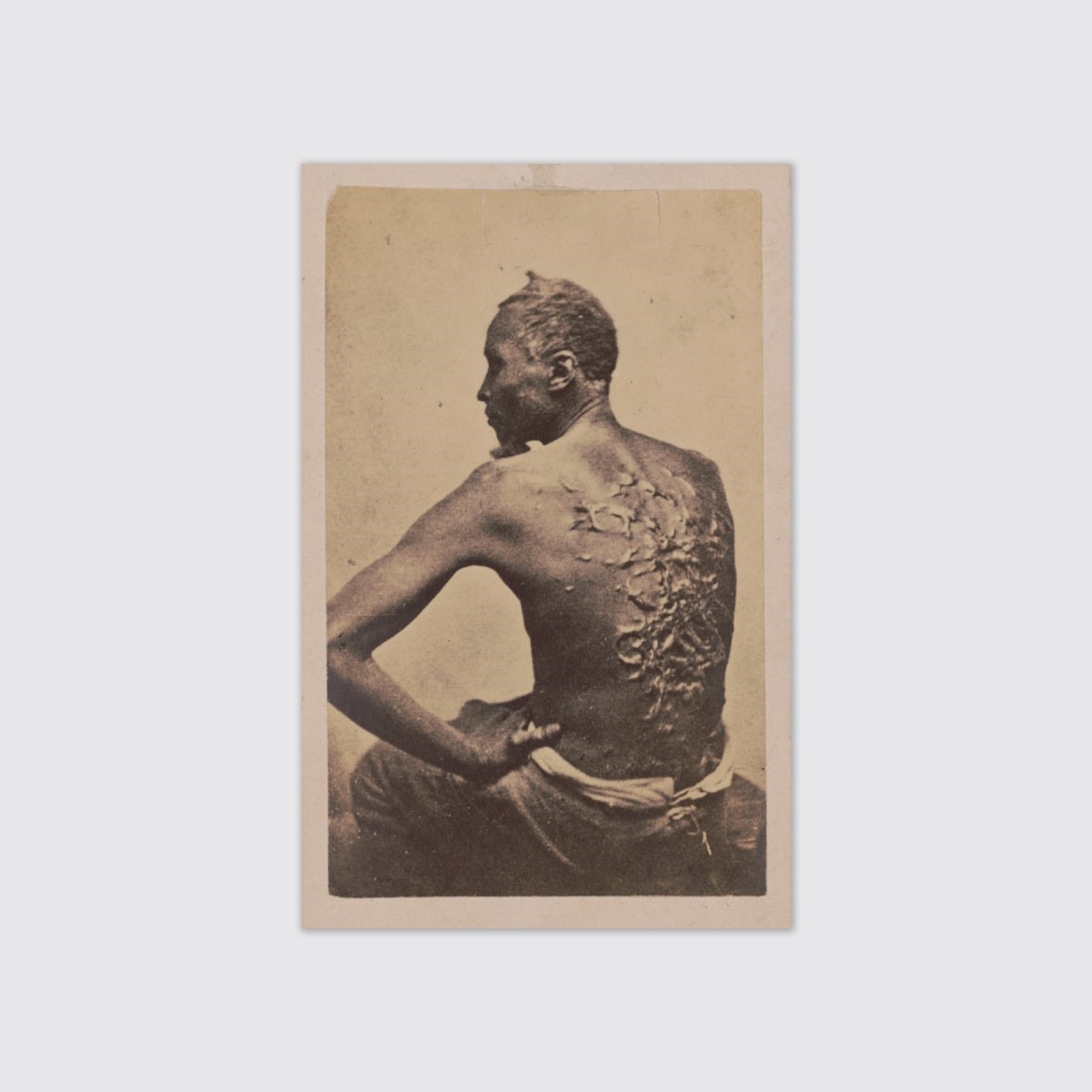

In an Instagram post, Emory explained that he felt compelled to leave because of how Supreme’s senior management had handled a collaboration with Arthur Jafa, a Black artist whose work sometimes depicts the violence of slavery. The marketing campaign was meant to include “the depiction of Black men being hung and the freed slave Gordon pictured with his whip lashes on his back,” according to Emory. (The latter image is likely a reference to a well-known photo in the National Portrait Gallery of a formerly enslaved man whose back has been disfigured.) Emory says the imagery was pulled without his consent, leading him to resign.

This past Tuesday, James Jebbia, Supreme’s head of HR and a representative from VF Corp, came to Emory’s house to talk through the reasons for his resignation. According to Emory, Jebbia admitted he should have talked to him before cancelling images from the Jafa collaboration, a decision made after one of the few other Black employees in Supreme’s design studio disagreed with its use.

From it’s earliest days, Supreme has engaged with aspects of Black culture, including hip-hop and streetwear. Jebbia chose its name from John Coltrane’s iconic jazz song, “A Love Supreme,” and T-shirts have featured the image of Malcolm X. But there have always been questions about how the brand, which was founded by a white man, could engage in Black culture without somehow appropriating it or exploiting it.

It’s a complicated question and one that came to a head in this alleged conflict over the Arthur Jafa collaboration. In Emory’s telling, he and the other Black designer had differing views on whether depictions of slavery should have a place in Supreme merchandise. The problem is that neither of these Black creatives were empowered to make the ultimate decision. Instead, according to Emory, it was Supreme’s predominantly white management that made the call. According to Emory’s Instagram post, the other Black employee has also resigned from Supreme.

Emory has used this incident to shed light on how systemic racism operates within fashion brands. In recent years, many large players in the fashion world have tried to partner with Black creatives. Louis Vuitton brought on Virgil Abloh as the creative director for menswear in 2018, a role he held until he passed away in 2021; it subsequently appointed Pharrell Williams for that role. Gap brought on Kanye West as a designer in 2020, but the collaboration collapsed in 2022. (In 2020, Gap also announced a collaboration with Telfar Clemens then unceremoniously backed out of it.)

Through Emory’s posts, he suggests that it is not enough to have Black creatives in highly visible top roles. To create an equitable culture, you need to have a critical mass of Black employees throughout the organization, and these employees need to be empowered to make decisions.

Emory himself explains this in a recent interview he did with Justsmile magazine, which Dazed highlights in a post about Emory’s departure. “I would caution kids who care about the validation of these big conglomerates and media giants, because these conglomerates are banks,” he said. “This is late-stage capitalism. These institutions will finance a designer, an artist, a band, a director, a writer, or whatever to make something get more money than they put in.”

(3)